Why aren’t there any big chess trees?

It’s funny, that although chess trees are a common concept, there isn’t one that attempts to cover „all of it“. Since at least you are here looking for something like this, one would think that there is some sort of demand.

Would they be too big?

Well, Chess Maps are 22 A0 pages, that is 22 sqm. You may call that big. Maybe you have a room of that size at home. That much area is necessary to allow for readably sized diagrams. Which are a key feature, as the goal of Chess Maps is to make all 3000 named opening variations visible.

To keep the area as small as that there is no additional info included which would cover transpositions, alternative move orders, second names of variations or established yet nameless lines.

Too chaotic?

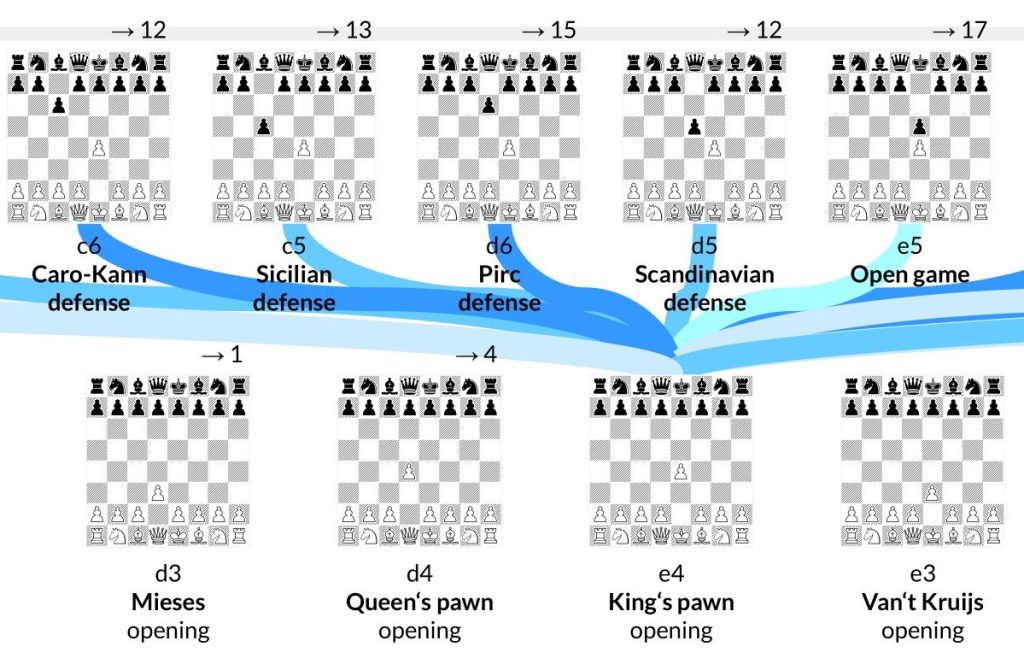

Well, to conquer arbitrariness in the design, there is a logic in Chess Maps, in which every variation has its natural place. A simple left-right logic. Where a line splits into two or more options, moves towards the left of the board (as White sees it), e.g., a pawn move to a3, are shown on the left, while, well, you get it already. Within one file the more advancing move comes towards the middle. That’s why in move one it is d3, d4, and then e4, e3.

There are also some number systems: Large grey move numbers, outlier numbers pointing to separate windows, page reference numbers with arrows. And a rough colour system is there – warm colours after 1.d4 and cold colours after 1.e4. Flank openings are wildly mixed to hold them apart. Call that chaotic, if you like.

Are they even of any use?

Studies and surveys point out that two out of three people prefer learning from visual material over reading textbooks. These same people use street maps for directions rather than a list of turns. So do I!

With Chess Maps it works almost like that. There is a logic-based geography in which you will easily find your way. Start with a landmark variation, that you have already heard of. From there, begin to explore. For the first ten or more moves compare variations, evaluate move options, and discover new lines for your own repertoire.

The learning part is your photographic memory’s job. Just rely on it. It remembers what you have seen, where that was, and how you got there. That’s how you memorize the most important positions in opening theory.

Is it too much work?

Well, this could be a reason. When I had the idea, I soon realised that it is a huge and complex task. That „one chess tree“ quickly turned out to be a dream – I would need many posters for it. More and more variation names sprung out of the internet. Time and again I had to redistribute them across an even bigger number of even bigger pages. And don’t get me started on handling outliers. It took many months.

But, and that’s the upside: I’m an expert now. You can be one, too! 🙂